|

|

|

| Time-lapse image registration using the local similarity attribute |  |

![[pdf]](icons/pdf.png) |

Next: Examples

Up: Fomel & Jin: Time-lapse

Previous: Introduction

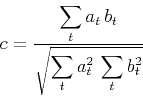

The correlation coefficient between two data sequences  and

and  is defined as

is defined as

|

(1) |

and ranges between 1 (perfect correlation) and -1 (perfect correlation

of signals with different polarity). The definition of the local

similarity attribute (Fomel, 2007a) starts with the observation that

the squared correlation coefficient can be represented as the product

of two quantities  , where

, where

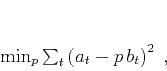

is the solution of the least-squares minimization problem

|

(2) |

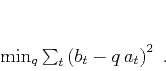

and

is the solution of the least-squares minimization

|

(3) |

Analogously, the local similarity  is a variable signal

defined as the product of two variable signals

is a variable signal

defined as the product of two variable signals  and

and  that

are the solutions of the regularized least-squares problems

that

are the solutions of the regularized least-squares problems

![$\displaystyle \min_{p_t}

\left(\sum\nolimits_t \left(a_t - p_t\,b_t\right)^2 + R\left[p_t\right]\right)\;,$](img12.png) |

|

|

(4) |

![$\displaystyle \min_{q_t}

\left(\sum\nolimits_t \left(b_t - q_t\,a_t\right)^2 + R\left[q_t\right]\right)\;,$](img13.png) |

|

|

(5) |

where  is a regularization operator designed to enforce a desired

behavior such as smoothness. Shaping regularization (Fomel, 2007b)

provides a particularly convenient method of enforcing smoothness in

iterative optimization schemes. If shaping regularization is applied

iteratively with Gaussian smoothing as a shaping operator, its first

iteration is equivalent to the fast local cross-correlation method of

Hale (2006). Further iterations introduce relative amplitude

normalization and compensate for amplitude effects on the local image

similarity. Choosing the amount of regularization (smoothness of the

shaping operator) affects the results. In practice, we start with

strong smoothing and decrease it when the results stop changing and

before they become unstable.

is a regularization operator designed to enforce a desired

behavior such as smoothness. Shaping regularization (Fomel, 2007b)

provides a particularly convenient method of enforcing smoothness in

iterative optimization schemes. If shaping regularization is applied

iteratively with Gaussian smoothing as a shaping operator, its first

iteration is equivalent to the fast local cross-correlation method of

Hale (2006). Further iterations introduce relative amplitude

normalization and compensate for amplitude effects on the local image

similarity. Choosing the amount of regularization (smoothness of the

shaping operator) affects the results. In practice, we start with

strong smoothing and decrease it when the results stop changing and

before they become unstable.

The application of local similarity to the time-lapse image

registration problem consists of squeezing and stretching the monitor

image with respect to the base image while computing the local

similarity attribute. Next, we pick the strongest similarity trend

from the attribute panel and apply the corresponding shift to the image.

In addition to its use for image registration, the estimated local

time shift is a useful attribute by itself. Time shift analysis has

been widely applied to infer reservoir compaction

(Hatchell and Bourne, 2005; Janssen et al., 2006; Tura et al., 2005; Rickett et al., 2007). Since the time shift has a

cumulative effect, it is helpful to compute the derivative of time

shift, which can relate the time shift change to the corresponding

reservoir layer. Rickett et al. (2007) define the derivative of time shift

as time strain and find it to be an

intuitive attribute for studying reservoir

compaction.

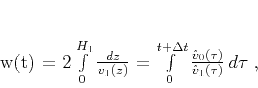

What is the exact physical meaning of the warping function  that

matches the monitor image

that

matches the monitor image  with the

base image

with the

base image  by applying the

transformation

by applying the

transformation ![$I_1[w(t)]$](img18.png) ? One can define the

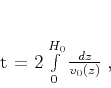

base traveltime as an integral in depth, as follows:

? One can define the

base traveltime as an integral in depth, as follows:

|

(6) |

where  is the base velocity, and

is the base velocity, and  is the base depth. A similar event in the

monitor image appears at time

is the base depth. A similar event in the

monitor image appears at time

|

(7) |

where  is the monitor depth,

is the monitor depth,  and

and  are seismic velocities as functions of time rather than depth, and

are seismic velocities as functions of time rather than depth, and

is the part of the time shift caused by the reflector

movement:

is the part of the time shift caused by the reflector

movement:

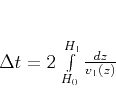

|

(8) |

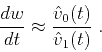

In a situation where the change of  with

with  can be neglected,

a simple differentiation of the function

can be neglected,

a simple differentiation of the function

detected by the local similarity analysis provides an estimate

of the local ratio of the velocities:

detected by the local similarity analysis provides an estimate

of the local ratio of the velocities:

|

(9) |

If the registration is correct, the estimated velocity ratio outside

of the reservoir should be close to one. One can connect

the local velocity ratio to other physical attributes that are

related to changes in saturation, pore pressure, or compaction.

We demonstrate the proposed procedure in the next section using several

examples.

|

|

|

| Time-lapse image registration using the local similarity attribute |  |

![[pdf]](icons/pdf.png) |

Next: Examples

Up: Fomel & Jin: Time-lapse

Previous: Introduction

2013-07-26

![]() that

matches the monitor image

that

matches the monitor image ![]() with the

base image

with the

base image ![]() by applying the

transformation

by applying the

transformation ![]() ? One can define the

base traveltime as an integral in depth, as follows:

? One can define the

base traveltime as an integral in depth, as follows:

![]() with

with ![]() can be neglected,

a simple differentiation of the function

can be neglected,

a simple differentiation of the function

![]() detected by the local similarity analysis provides an estimate

of the local ratio of the velocities:

detected by the local similarity analysis provides an estimate

of the local ratio of the velocities: